While Rosa Parks is often referred to as the “mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” Septima Poinsette Clark captured the role of grandmother. Clark’s work played an integral role in educating and enfranchising thousands of African-Americans throughout the South. Her “Citizenship Schools” empowered marginalized black communities to push back against Jim Crow laws and fueled the grassroots of the Civil Rights Movement.

“The greatest evil in our country today is not racism, but ignorance,” Clark wrote in 1965.

Her work targeted both.

Born in Charleston, S.C., in 1898 to a father who was a former slave, Clark grew up in a home that valued education. From an early age she studied hard and demonstrated an aptitude for learning before becoming a teacher. Because Charleston did not allow black teachers to teach white or black students, her career began in Johns Island, S.C., in 1916. Clark started a petition in 1919 to allow black teachers in Charleston. Eventually, two-thirds of the city’s black population signed the petition and the ban was overturned.

Clark married Nerie Clark in 1920, but he died of kidney failure five years later. She continued to teach in Columbia, S.C., and became more involved with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which sought equal pay for black and white teachers in South Carolina. Her salary increased threefold when the case was finally won in 1945.

In 1947, Clark took up another teaching post while maintaining her NAACP membership. However, in 1956, South Carolina made it illegal for public employees to belong to civil rights groups. Clark refused to renounce the NAACP and lost her job.

Clark continued her passion for education and equality at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. The Highlander School featured integrated workshops on citizenship and civil rights. The school trained several prominent members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), including Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy and John Lewis.

Clark found a niche at Highlander where she drew on her teaching experience in rural South Carolina to instruct literacy courses. In a short time, she turned sharecroppers and other uneducated and impoverished black residents into literate voters who could pass tests. Among the ways Southern whites kept blacks from voting was through literacy exams. Clark’s efforts allowed many blacks to overcome that barrier.

Unfortunately, Tennessee revoked the school’s charter, closed its buildings and arrested teachers on bogus charges. Upon her release from jail, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. invited Clark to continue her work with the help of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the “Citizenship School” model bore out. The schools became a monumental success, by filling educational gaps created by segregated school systems that made black students the last priority.

In 1957, Clark worked with her cousin Bernice Robinson and Esau Jenkins, a bus driver from Johns Island, S.C., to continue the citizenship schools. They opened one on Johns Island in South Carolina that specialized in state election laws and voting.

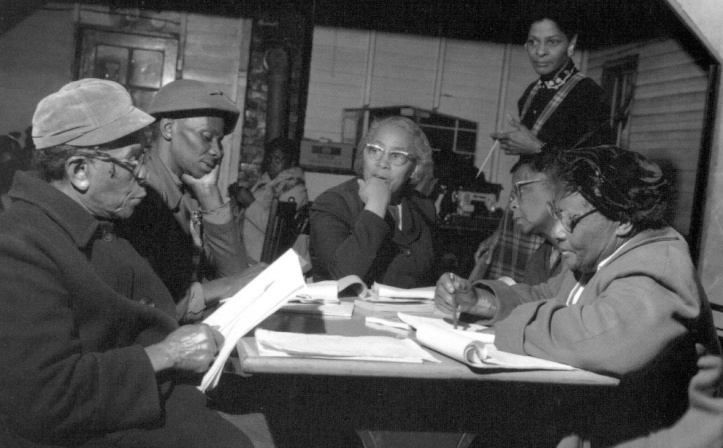

Clark and her cadre of teachers spread the citizenship class throughout the South. Classes and schools often occurred in the back of a room or shop to elude racist whites. Many of Clark’s teachers had recently learned to read themselves, which was a model that helped Clark overcome challenges connecting with older reluctant audiences. Clark’s citizenship schools not only registered voters, they also developed new leaders that could push for civil rights. More importantly, the school gave newly educated African-Americans the confidence to stand up against segregation and participate in the democratic process.

“The basic purpose of the citizenship schools is discovering local community leaders…It is my belief that creative leadership is present in any community and only awaits discovery and development.”

With the help of the the citizenship schools, black voters expanded throughout the South. By 1970, two million African-Americans had registered to vote.

Dr. King acknowledged Clark when he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 by insisting that she accompany him to Sweden.

She died in Johns Islands, S.C. in 1987.